Realtors often say that when you’re trying to sell a house, you should bake a fresh batch of homemade cookies before a showing to potential buyers. While some realtors may just want the cookies, the good ones know that the smell of fresh baked cookies transports us back to our childhoods, and gives us a feeling of home, which they can cynically abuse to get you a good price on your house.

Scent is a very powerful memory stimulator. The brain’s funny that way.

Another interesting thing about the brain: it works super hard during sleep. While the body rests, the synapses are firing wildly, making new connections. In fact, ‘sleeping on it’ is a great way to come up with new insights.

So, what if we put these two ideas together?

Well, in 2012, Dutch scientists did exactly that. Professor Simone M. Ritter from Radboud University and her team figured out how to use scent association to steer your sleeping brain. In short, you can sleep as long as you like, and still be productive.

A dreaming brain is smarter than you might think

Let’s take a step back. I hear you asking, “but isn’t a sleeping brain like a boat without a rudder, only capable of producing rambling dreams without any value whatsoever?”

Nope. The sleeping brain is hardwired to freely associate in unexpected ways. Sure, that makes dreams seem illogical and rambling, but it’s also the most uninterrupted super-brainstorm you’re capable of. There have been many studies on this. For example, let’s take a look at one done in Germany in 2004 by Ullrich Wagner and his team.

The scientists subjected their test subjects to a series of complex tests. After performing all of the tasks, the test group slept for 8 hours, while a control group got to spend 8 hours doing other things. Then they took the tests again, to see if they had improved.

But there was a trick! The researchers had hidden a shortcut in the tests that would let a person jump straight to the answers. They wanted to know what group would be better at finding that shortcut: those who slept, or those who got to think about the test while doing something else? A respectable 23% of the control group figured it out, but an astounding 60% of the group who slept on the problem managed to find the shortcut.

Sleep provides an opportunity to think of a problem in a variety of different angles, unfettered by the restrictions we have to put on our waking mind. So, basically sleep is your best friend for thinking outside of the box.

Now, back to our Dutch friends

So, back to our 2012 Dutch study, researchers from Radboud University Nijmegen wanted to take this a step further, and find a way to harness that night time thinking.

They wanted to know: can we use all that bi-lateral, creative thinking that we do for free while we sleep, and use it in a productive way? How can we make sure to ‘sleep on’ a problem in a focused manner and come up with a creative solution?

The experiment’s central hypothesis was that because of scent association, the test group would be prompted to be more focused on this specific problem while they slept.

First things first: how do you measure creative thinking anyway? Well, there’s a test for that. The “Unusual Uses Task test” is a widely used measure of creativity. In it participiants are given 2 minutes to come up with as many creative solutions for a problem as they can. Like: how many ways can you use a brick, or a paperclip, or whatever.

So the researchers decided that to measure creative thinking in your sleep on a certain topic, you just make someone do an “Unusual Uses Task test” in the morning on that topic.

Next, we need a topic that requires creative thinking. Something complex, preferably related to a real world issue, that can be approached from different angles. The Dutch researchers decided on asking “how do you get volunteers motivated?” Focus your brains on that, test subjects!

Finally, the real test is to determine how to kickstart the brain into thinking about motivating volunteers, and not about, say, your love life or yesterday’s movie? Here the real new idea kicked in. The researchers decided to use scent.

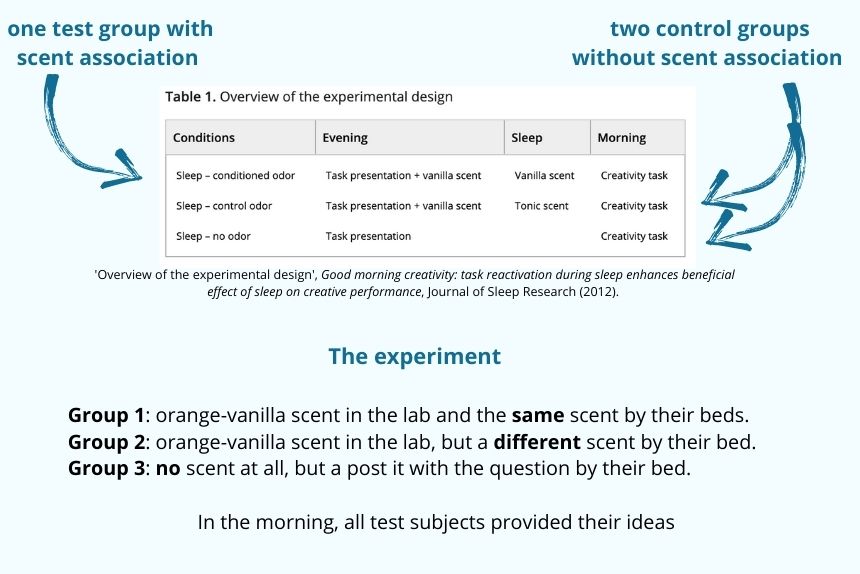

The subjects were placed in room and shown a 10 minute video explaining the problem. In that room, they placed an orange-vanilla scented air freshener. The participants were then sent home to sleep on the problem. When they woke up, they would logon to a system and immediately enter all of the solutions to the problem they could come up with in 2 minutes.

But here’s the kicker – that test group got the same air freshener to put on their night stands. The idea was that the scent association would steer the dreaming brain to thinking about all those volunteers and how to motivate them, ideally leading to the subjects having creative solutions in the morning.

Of course there were control groups, as well. One control group got the same task, with orange vanilla scent in the room, but were given a different smelling air freshener to take home. Sure, their bedroom would smell nice, but there would be no association with watching the video on how to motivate volunteers. A second control group got the same task, but this time without any fragrance involved. They were however asked to put a post-it note on their nightstand with the problem written on it.

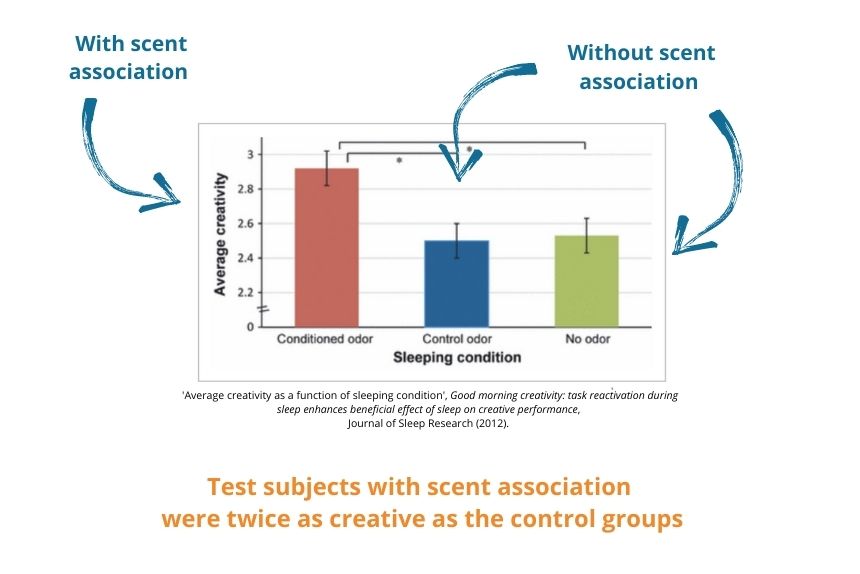

First thing the next morning, all participants went online and gave the researchers all the ideas they could come up with in 2 minutes. To make sure that real creativity was measured, and not just ‘how fast can you type’, the researchers didn’t go on the amount of ideas, but measured the overall creativity of the ideas.

To do this, first an independent panel trained in judging the “Unusual Uses Task test” gave each idea a score from 1 to 5 on how out-of-the-box the idea was. In the example ‘how many uses can you find for a brick?’, an obvious answer would be ‘build a house’. More creative would be ‘use it as a pen holder’. Once the answers were evaluated, the total score was divided by the number of ideas. And voila: a creativity score was given to the sleeping thought process.

So how did the people do? Surprisingly well! The test subjects with the scent association were twice as creative as the control groups. Even putting the problem on a post-it as a reminder (a common tip for dreaming on a problem) didn’t do as well.

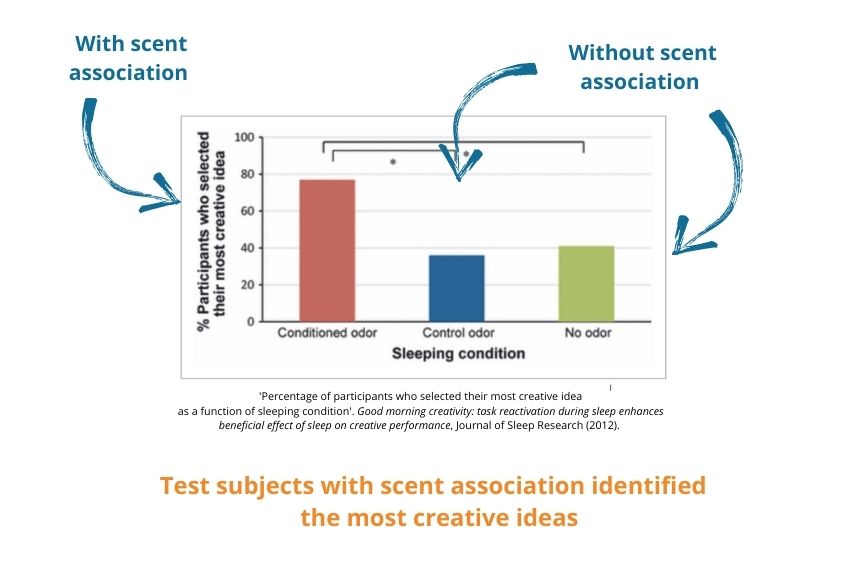

But the researchers went one step further. They realized that in real life, it doesn’t matter how many great ideas you have, if you’re just going to dismiss them as ‘silly’ or ‘stupid’. The only ideas that matter, are the ones that you recognize as brilliant, and put into action. As the researchers put it in their paper:

“We included this measure, as in real‐life settings most creative processes entail both idea generation and idea selection. For example, when trying to find creative solutions for a problem, one‐first has to generate ideas and, thereafter, one has to select the one that is most promising. For the idea generation phase, the measure of interest was the participant’s average creativity score. Concerning the idea selection phase, we were interested in whether a participant’s selection of the most creative idea was in accordance with judgment of trained raters.”

So, how good would the participants prove to be in picking out their most creative idea? Again, the scent association group stood out. The test subject whose brains were kicked into gear with smell, did twice as well when asked to identify their most creative idea.

Conclusion: the smell association got results. The experts judged the test group to be twice as creative, and twice as good at judging the strength of their own ideas. Sure, this was a small test group, but it definitely opens the door for more research, and some solid field testing at home. Knowing this can give you an edge when it comes to creative thinking.

What if it’s just scents in general?

The researchers wanted to account for that, too. So, as mentioned, the third group discussed above had one scent in the room while watching the video, and a second totally different scent in their bedrooms that night. There would be some nice scents, but no association.

This third group showed no real difference in effectiveness when compared to the control group that had no air fresheners at all.

Does the scent matter?

The researchers choose orange vanilla because they liked the smell of orange vanilla. It was effectively random. In my experience the scent doesn’t really matter — it is about the association to the scent being used. I would say use something that you would like to have in your bedroom, not too strong or overpowering. Personally, I put a little lavender diffuser next to my laptop when I am working on a project, and put the same lavender next to my bed.

Of course, I make sure that I don’t smell it when watching a movie, otherwise I might dream about the movie instead. Keep it focused!

Wow, has anyone checked the other senses?

Similar research has been done in other parts of the world with sound as a trigger. This has the unfortunate side effect that it’s more likely to wake you, but it seems to work as well. Trying this at home, some people use music to trigger their minds. The bonus of a nice scent is that it doesn’t wake you or your partner as easily. And even if it doesn’t quite work out for you as intended, you will have a lovely smelling bedroom.

On the other side, however, some people suffer from varying degrees of anosmia (the inability to smell), and may find sound to be a good option.

Are there downsides?

I haven’t found any downsides yet, but there are some things to keep in mind. Firstly, you only have the one brain, and it’s going to be focused on what’s most on your mind or in your heart. So no amount of essential oil is going to make you dream of work when you are in the middle of a relationship crisis. Understanding that, be sure to pick the right time for trying this out.

Meanwhile, thinking in your sleep is great for out of the box, creative ideas. But a creative idea is not automatically a good idea. That’s where rational thinking comes in: to judge which idea is gold, and what can be filed away as ‘not applicable right now’.

Also, the study itself didn’t have thousands of participants. This was basically a preliminary study, but the results show that the concept is worth more investigation. But because it’s so easy to set up the test, we can all be beta testers for the sleepthinking concept from the comfort of our own beds.

Awesome, can you teach me how to do this?

Personally, I think this is an awesome life hack. We get to be smart and sleep in at the same time! For example, when you’re working on a task that could benefit from some extra creativity, try having a scented oil diffuser next to your laptop, and put the same diffuser on your night stand while you sleep. Feel free to turn off your alarm clock – your brain is working, so let’s not disturb all that subconscious intelligence. Is that an excuse to sleep in? Oh yes.

In the morning, write down your first 20 ideas, or dreams, or thoughts. There might be some gold in there. And if not: feel free to try again! Testing this out with clients, we have found that sleeping on a topic 3-4 nights gives the best results.

In this study, only scent was looked at. But there’s a follow up question: what if you combine different techniques? What if you, for example, would have scent as a trigger, but you also write the problem down, and start meditating on it right before you fall asleep? Would that get even better results? The answer is that I don’t know. It wasn’t tested in this study – PhD students, that’s a hint!

The possibilities are wide open to layer on techniques to induce some sleep thinking. Like meditating on the question before falling asleep, keeping a post-it of the question on your night stand, under your pillow or whatever else feels right. I would love to hear your results.

References

Sleep inspires insight, Wagner, U., Gais, S., Haider, H., Verleger, R. and Born, J. in Nature, 2004, 427: 352-355.

Good morning creativity: task reactivation during sleep enhances beneficial effect of sleep on creative performance, Simone M Ritter, Madelijn Strick, Maarten W Bos, Rick B van Baaren, Ap Dijksterhuis, in Journal of Sleep Research, 2012 Dec;21(6):643-7.